Trilobite

Exoskeleton Origins

Trilobite

Exoskeleton Origins

One

of life's most important evolutionary adaptations was the emergence

of the external skeleton, or exeskeleton, presumably in the

earliest part of the Cambrian known as the Cambrian Explosion.

It is not

a coincidence that the early Cambrian marks the beginning

of the "macroscopic fossil record". That trilobites

first appear in the fossil record already

highly diverse

and spread geographically is precisely due to its readily

preserved, hard external skeleton. Most trilobite fossils are,

in fact,

the preserved

exeskeletons. Only under rare circumstances have the soft

body parts of trilobites (and other arthropods) been preserved

as

fossils. The Precambrian fossil record is extremely poor,

and many putative precambrian fossil equivocal at least partly

because that lacked hard parts.

There

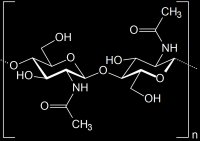

are different hypotheses on the origins of the arthropod exoskeleton

in the Precambrian. There is  concensus that Arthropoda is monophyletic,

and that the Onychophorans (velvet worms) and Arthropoda are

sister groups descended from

annelids (phylum Annelida), and a member of Superphylum Ecdysozoa,

a clade (Aguinaldo,

1997) with a common ancestor comprising animals with a cuticle

that periodically molted as the animal

grows. Interestingly, the Onychophorans, besides leg having

similar structure, locomotion, and embryology similar to myriapods

(Anderson,

1973), have exoskeletons. Ribosomal RNA analysis of velvet

worms and other arthropods also suggests close

affinity

between

them (Ballard et

al. 1992). The velvet worm exoskeleton is a one mm thick chitin

and protein layer resembling that of some arthropods. Without

a doubt, arthropod phylogeny is problematic, but that the trilobite

exoskeleton has origins in Phylum Onychophora is plausible conjecture.

concensus that Arthropoda is monophyletic,

and that the Onychophorans (velvet worms) and Arthropoda are

sister groups descended from

annelids (phylum Annelida), and a member of Superphylum Ecdysozoa,

a clade (Aguinaldo,

1997) with a common ancestor comprising animals with a cuticle

that periodically molted as the animal

grows. Interestingly, the Onychophorans, besides leg having

similar structure, locomotion, and embryology similar to myriapods

(Anderson,

1973), have exoskeletons. Ribosomal RNA analysis of velvet

worms and other arthropods also suggests close

affinity

between

them (Ballard et

al. 1992). The velvet worm exoskeleton is a one mm thick chitin

and protein layer resembling that of some arthropods. Without

a doubt, arthropod phylogeny is problematic, but that the trilobite

exoskeleton has origins in Phylum Onychophora is plausible conjecture.

Trilobite Exoskeleton Prosopon

Prosopon

are features on the trilobite exoskeletons that are usually

smaller and include nodes,

perforations, pitting, and pustules, and generally exclude larger

features such as pleural

spines. In general, the purposes of prosopon as evolutionary

adaptations features remain equivocal. They have some use as

diagnostic

features

in identification

and classification, but caution must be used as proposon attributes

are in a broad sense shared across all of Trilobita. The ubiquitous

nature of the prosopon suggest they arose independently and

multiple times in different orders exposed

to the same environments and selective pressures, an example

of parallel evolution.

Tubercles

Tubercles

are found in many trilobite families and species, and are particularly

common and pronounced in orders Lichida

(see Artinurus

boltoni) and Phacopida. Tubercles are also prevalent among

Proetids (see Proetus

tuberculatus morocensis , a trilobite actually named the

tubercules on its cephalon. Why tubercles evolved is uncertain,

but scientists have

conjectured

they

may

have provided

a measure

of camouflage,

especially when combined with color patterning. Similarly, tubercles

may have made it more difficult for tentacled predators such

as nautiloids to get a firm grasp on them. Tubercles vary in

morphology small dome-like nodes to short spikes. Tubercles,

especially smaller ones, are often called granules, and terminology

such tuberculose or granulous exoskeleton will be seen.

Tubercles

are found in many trilobite families and species, and are particularly

common and pronounced in orders Lichida

(see Artinurus

boltoni) and Phacopida. Tubercles are also prevalent among

Proetids (see Proetus

tuberculatus morocensis , a trilobite actually named the

tubercules on its cephalon. Why tubercles evolved is uncertain,

but scientists have

conjectured

they

may

have provided

a measure

of camouflage,

especially when combined with color patterning. Similarly, tubercles

may have made it more difficult for tentacled predators such

as nautiloids to get a firm grasp on them. Tubercles vary in

morphology small dome-like nodes to short spikes. Tubercles,

especially smaller ones, are often called granules, and terminology

such tuberculose or granulous exoskeleton will be seen.